6 Best Retirement Calculators (#1 is Free)

Some of the links in this article may be affiliate links, meaning at no cost to you I earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase or open an account. I only recommend products or services that I (1) believe in and (2) would recommend to my mom. Advertisers have had no control, influence, or input on this article, and they never will.

Retirement calculators can help us plan and prepare to retire. When we are years away, these online tools can help us determine how much we should be saving. As we approach our time to retire, they can help us understand how much we can spend each year in retirement without going broke.

Not all retirement tools, however, reach the same result. They take different approaches to what is a complex series of calculations and assumptions. One study examined five popular retirement planning software packages and found stark differences in outcomes. As a result, it recommended that individuals use “multiple programs before implementing an action plan based on the results.”

To that end, here is a list of the best retirement calculators. Note that I have used each of these tools for years, as well as many others that didn't make the list.

Editor’s Top Picks

Of all the retirement planners available today, two stand out among the rest:

- Empower–Previously called Personal Capital, it’s both free and comes with a robust set of features. Its retirement planner enables you to model everything from social security to pensions to one-time income (e.g., inheritance) and expenses (e.g., home renovation) during retirement. You can create multiple scenarios and run Monte Carlo simulations to see your chance of financial success (i.e., not running out of money).

- New Retirement–This tool allows you to model virtually every aspect of retirement. It projects future income, expenses, and net worth. You can set income and expenses on a monthly, yearly, or one-off basis. It can model social security, pensions, and even Roth IRA conversions. There is an annual fee, although New Retirement does offer a free trial.

Best Retirement Calculators

What follows are my top 6 picks. Note that the first two are also retirement planners, meaning they have far more robust features than a simple calculator. The final three options are retirement calculators only. The inputs are much more limited, but these tools give you a quick estimate of when you can retire.

1. Empower

Best free retirement calculator

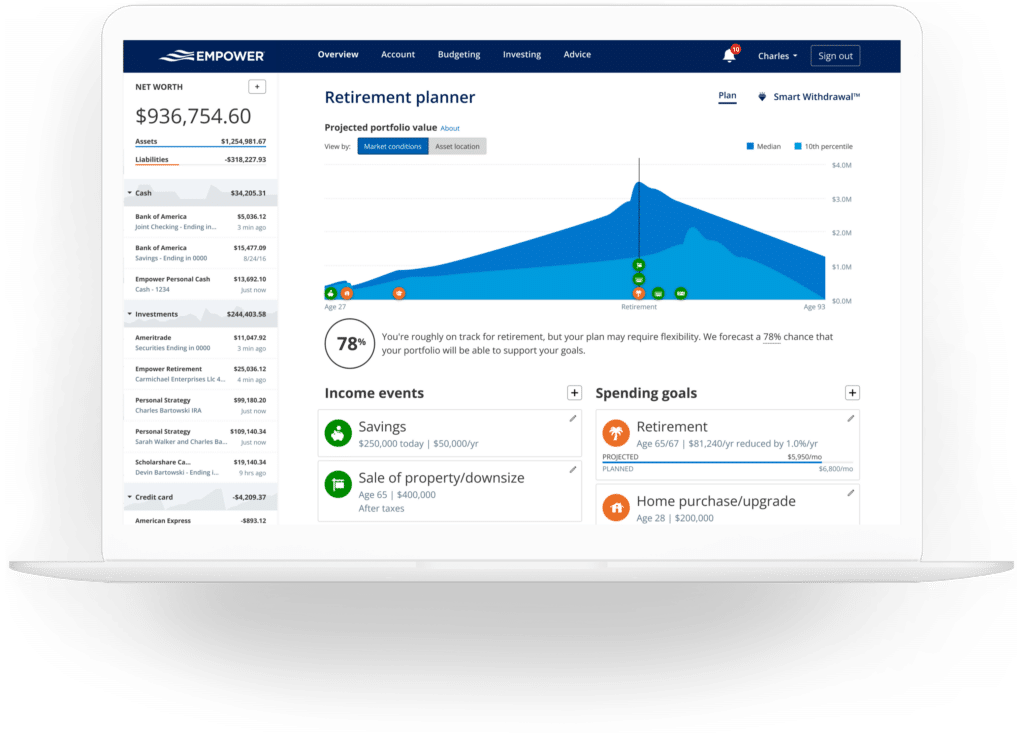

Empower is my favorite investing and retirement tool. In addition to being totally free, it's extremely easy to use and rich in features. Once a user connects their 401k, IRA, and other investment accounts, Empower pulls all the data from the accounts into its Retirement Planner.

The Retirement Planner then allows users to model both income events (e.g., savings, sale of real estate, social security, pensions) and spending goals (e.g., retirement spending, travel, education). Users can also set up multiple scenarios to compare, such as retiring at different ages. Empower then runs the data through a Monte Carlo simulation and reports the likelihood of the plan's success.

Unique Feature: Users can create multiple scenarios (e.g., different retirement dates, different social security strategies) and compare how successful each will be.

2. New Retirement

Most detailed retirement analysis

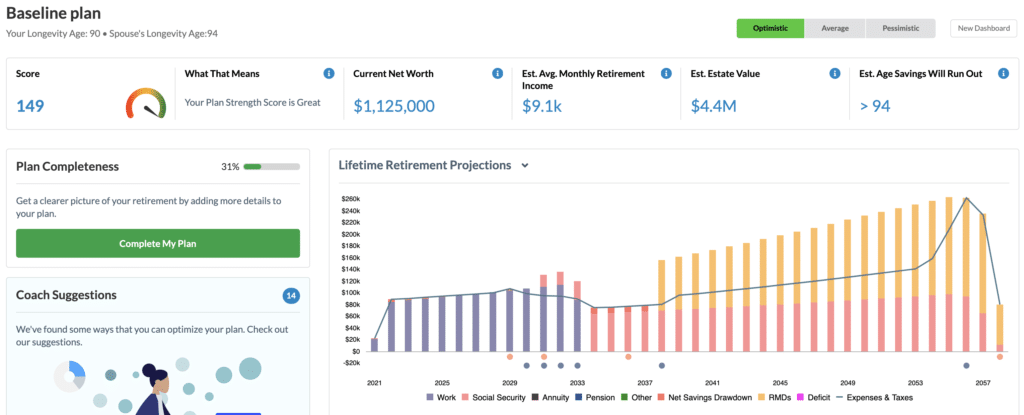

New Retirement is not for the faint of heart. The tool, which has both a free and paid version, enables users to model just about every aspect of retirement. For example, users can model social security claiming strategies, medicare coverage, annuities and pensions.

New Retirement handles the complexity of retirement planning in two ways. First, users can follow a quick start guide, answer a few simple questions, and have a complete snapshot of their retirement readiness in under five minutes.

Following that, users can dive into the details of everything from future healthcare costs to retirement savings contributions. New Retirement enables users to link investment and retirement accounts or enter them manually.

New Retirement offers three plans ranging in cost from free to $396 a year.

Unique Feature: New Retirement includes a Roth IRA conversion calculator to help users determine when and how much of a traditional IRA should be converted to a Roth IRA.

3. Vanguard's Retirement Nest Egg Calculator

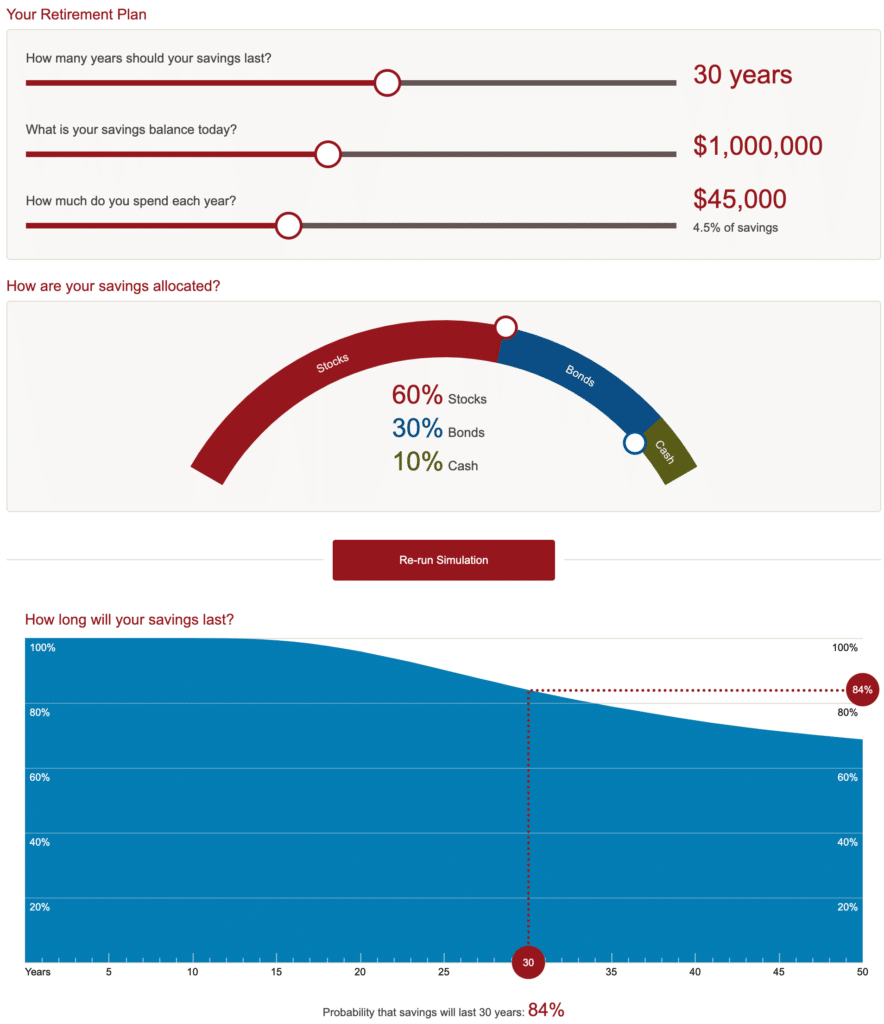

Vanguard's retirement calculator seeks to answer one question–how long will your retirement nest egg last? It requires just four pieces of information:

- Length of retirement (e.g., 30 years)

- Current savings balance

- How much of the balance you'll spend each year

- Your stock/bond/cash allocation

With these four data points, Vanguard runs 100,000 simulations and provides the chance of success. Here's an example:

The calculator is very easy to use and provides useful information to assess one's retirement readiness.

4. NetWorthify

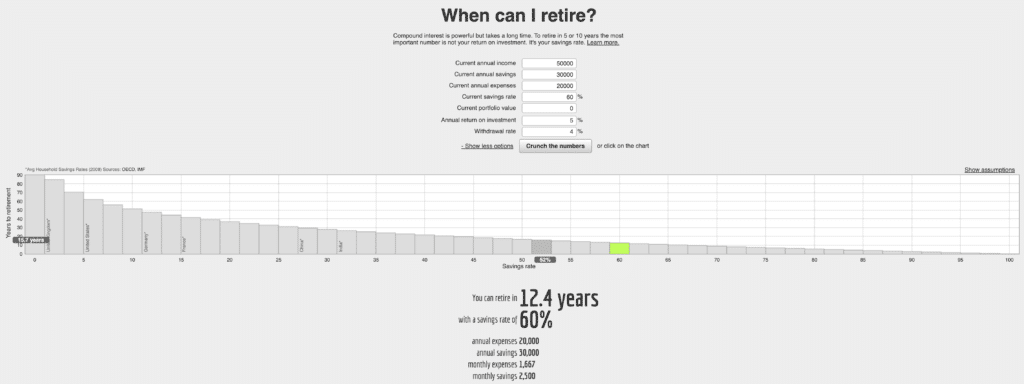

NetWorthify is designed for those wanting to retire early, although it works with traditional retirements, too. Simply enter your income, annual savings, and total savings, and NetWorthify estimates how long until you can retire. It's free to use.

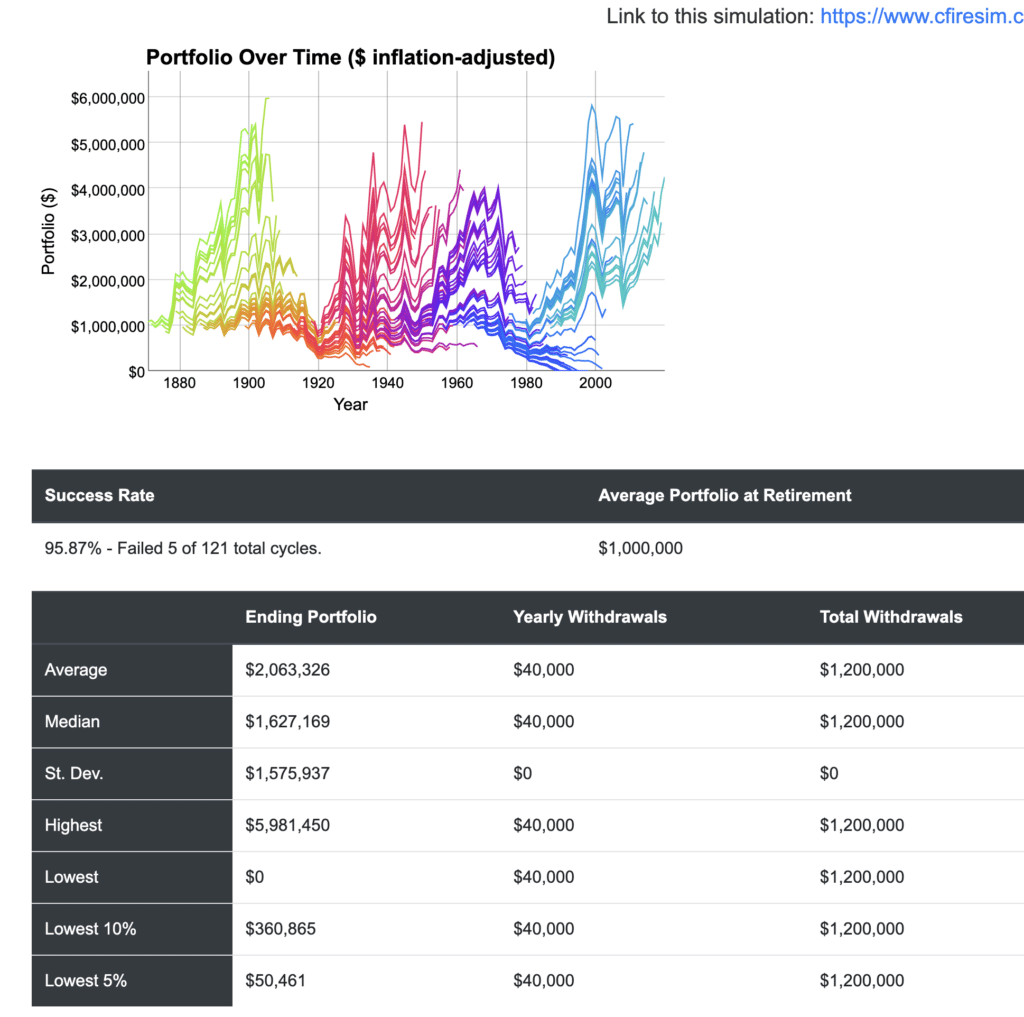

5. cFIREsim

Another free option that I like a lot is cFIREsim. You enter some basic information such as when you plan to retire, current savings, income, asset allocation of your investments, and social security values. cFIREsim then calculates the likelihood of your success.

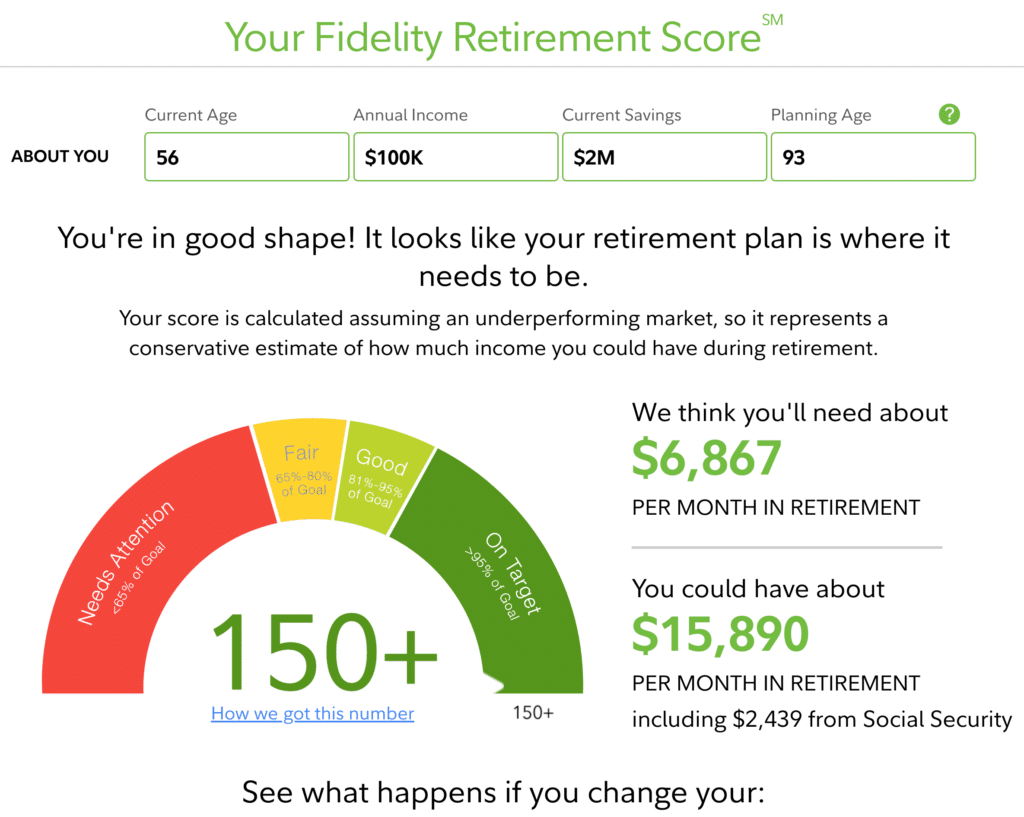

6. Fidelity's Retirement Score Calculator

Fidelity's Retirement Score Calculator estimates the percentage of your expenses in retirement that can be covered by your retirement savings. The calculator requires just a few pieces of information, including your age, salary, savings balance, and investment style. With this data, the calculator generates a retirement score:

Note that the calculator factors in an estimate of social security benefits.

Other Retirement Calculators Worth Considering

The following retirement tools didn't make our list but still may be worth checking out. In some cases, I'm continuing to evaluate them, and some make the “best of” list in the future.

- FireCalc

- T. Rowe Price

- MaxiFi Planner

- Ultimate Retirement Calculator

- ESPlanner

- AARP

- Fidelity Full View

- Betterment Retirement Savings Calculator

- Charles Schwab Retirement Calculator

- Dave Ramsey's Retire Inspired Quotient Tool

- Stash Retirement Calculator

- The Complete Retirement Planner

Retirement Calculators Not Worth Considering

Here are retirement tools that I believe aren't worth our time. I list them here to keep a record of what I've looked at and so that readers know I've considered and rejected these options.

- Flexible Retirement Planner–Too many ads on the site and the planner must either be downloaded (Windows only) or used with Java Web Start.

FAQs

Are Retirement Calculators Free?

Most retirement calculators, unlike retirement planning software, are free.

What's the difference between a retirement calculator and retirement planning software?

Retirement planning software is more robust than a retirement calculator. They can factor in far more details, such as different social security claiming strategies, Roth conversions, and Medicare premiums. They can also run ‘what-if' scenarios. In contrast, a retirement calculator uses just a few inputs to give one a high-level view of their retirement readiness.

What is the best retirement calculator?

While the best retirement calculator will vary based on one's personal preferences and specific goals, I believe Empower's Retirement Planner is the best. It's free and offers a good combination of features and ease of use.

Rob Berger is a former securities lawyer and founding editor of Forbes Money Advisor. He is the author of Retire Before Mom and Dad and the personality behind the Financial Freedom Show.